Recursion is a basic topic in computer science, and thankfully not well known in controls circles, outside of people who have had exposure to more traditional forms of programming. Because we here at majorfault are always interested in disasters that can fault PLCs, I've decided to take a closer look at what it might look like on a Rockwell platform. For science, and fun, of course.

0. A quick reminder (or tutorial) on recursion

For those joining in without a basic computer science background or who have forgotten the details, a recursive function is a function divided in two parts : the recursive case and the base case.

- Recursive case: This is the branch of execution where the function will call itself, "winding" itself on the call stack and deferring the final calculation. In essence, each call acts as a small piece of the final calculation.

- Base case: This is the branch of execution where the function has reached a point where the problem either cannot be further split into pieces or can be easily calculated. It will return the result of this final calculation, causing the stack to "unwind" until all the pieces have been calculated and the final result can be returned.

A simple example of recursive thinking is the following : imagine we pick a random positive integer n. We want to know the sum of all the integers between 1 and this number, inclusively. To abbreviate the notation, let's call sum(n) the sum of all the integers between 1 and n, inclusively.

To solve this, we cut the problem into small pieces, recursively using my sum() thing until we hit a point where we cannot cut the problem anymore.

To wit, in fact, sum(n) is equal to n + sum(n - 1).

What's sum(n - 1)? We don't know that, but we can calculate it : it's (n - 1) + sum((n - 1) - 1).

What's sum((n - 1) - 1)? We still don't know that, but we do know it's ((n - 1) - 1) + sum(((n - 1) - 1) - 1).

And so on it goes until we ask the question : what's sum(1)? We know what that is : the sum of all the integers between 1 and 1 is 1. Because we can dictate the result, we have no further need for subdivisions, and we can use this result to compute the rest of our calculations.

For n = 4, the process looks like this:

- sum(4) = 4 + sum(3)

- sum(3) = 3 + sum(2)

- sum(2) = 2 + sum(1)

- sum(1) = 1, and thus:

- sum(2) = 2 + 1 = 3

- sum(3) = 3 + 3 = 6

- sum(4) = 4 + 6 = 10

If you think this is clunky, you're right. The truth of the matter is that nearly all recursive algorithms have an iterative equivalent (in this case a simple for loop), and generally, iterative equivalents are faster or simpler than their recursive versions. Recursion shines in situations where the amount of calculations to do is hard to know in advance, for example in nested or tree-like data structures, because in these environments they are easier to reason about.

1. Why?

First, let us list the reasons why you would use recursion in PLC platforms :

Now, the reasons why you shouldn't use recursion in PLC software :

- There are very few recursive algorithm applications in an industrial setting which wouldn't make more sense and be easier to implement as their iterative equivalents.

- Recursion can make the scan time of a platform unpredictable, leading to avoidable crashes if the recursion takes too long to compute, and making time-dependent applications unstable in behaviour.

- Stack overflows are also a thing in PLCs, leading to another source of avoidable crashes.

- Because no one ever uses recursion in a PLC, no one will understand what the hell is happening, except you. And you will forget in 6 months.

- This is pretty much a hack, so it is unwieldy to use.

For good reason, the PLCopen guidelines plainly prohibit recursion.

Lest you still believe that Rockwell PLCs are a rigid platform devoid of any modern programming conveniences, it is actually possible for subroutines to call themselves (as an aside, this is prohibited for AOIs - you can't recursively call an AOI instance).

However, the way this works is a bit different from what one might expect. In essence, while there is a kind of call stack (because the program knows where in the program it must return after completing a subroutine), there is no memory stack to accompany it. I will explain what this means below.

2. Calling subroutines

This topic will require a bit of an exploration on how calling subroutines in Rockwell actually works.

We are accustomed to using subroutines as a simple code organization feature. We don't think of subroutines as functions or even procedures. We create a "program" inside a "task", with a "main routine", and in this "main routine" we list our "subroutines" that we sequentially and unconditionally call with the JSR instruction. We use these pretty much only for their side effects. In other words, we don't really care about what is returned from the subroutine (we usually don't return anything), we just want it to execute and do things.

However, before AOIs existed, subroutines were designed to be pieces of reusable code. Subroutines can take input parameters and return values via output parameters. However, as a code reuse mechanism, they have a glaring weakness : subroutines do not have a scope. The most restrictive scope (sans AOIs) is at the program level. Therefore, any variable declared in a subroutine is minimally shared throughout the program. This means that other subroutines, and even other calls of the same subroutine, share memory.

This weakness makes them excruciatingly hard to debug because the programmer cannot easily see the memory context in which the call is executed. This is the shortcoming that AOIs were designed to fix, as they do have a local scope.

In practice, to use a subroutine as a reusable code piece, there is a certain flow:

We use a JSR instruction to call a given subroutine. Optionally, we can pass a number of input and output parameters (up to 40). In ST, we have to specify the number of inputs we pass, so the compiler knows which tags are inputs and which are outputs. Here is an example of a JSR call where n is the number of input parameters and m the number of output parameters.

JSR(MyRoutine, n, Input_1, Input_2, ..., Input_n, Output_1, Output_2, ..., Output_m);

The called subroutine then receives the inputs using the SBR instruction. This instruction takes the JSR input tags and passes by value to "local" tags. The SBR looks like this :

SBR(LocalInput_1, ..., LocalInput_n);

The purpose of this copy mechanism is to buffer the input parameters into memory so that they do not change if the PLC has to stop computing the subroutine. For example, maybe a periodic task has fired, in which case the PLC will interrupt its scan of this subroutine, do other stuff elsewhere, and perhaps somewhere in this periodic task, the input parameters of the original sub are changed. As discussed, since this memory isn't truly local, the program can still mess with it - this is up to programmer discipline.

You do whatever operations you need to do using the LocalInput_n tags, whose values are originally copied from the Input_n tags passed in the JSR. You then return the result using RET, which does the "opposite" operation : it takes m "local" tags and passes them by value to the return tags specified in the JSR. The "Output" tags you've passed to the JSR will receive the values of the "LocalOutput" tags passed to the RET.

RET(LocalOutput_1, ..., LocalOutput_m);

When writing in structured text, there are some syntactic caveats that programmers must keep in mind :

- JSR, SBR, RET take tags or literals, not expressions. So you cannot do this :

JSR(MyRoutine, 1, Input_1 + 1); - These are C-style code blocks with return parameters, not real functions. They do not truly return values. You can't do this :

MyTag := JSR(MyRoutine, 1, Input_1); - As mentioned, all "local" variables are shared across calls (and further beyond). Effectively, they are all static. This means that the "recursive calls" don't carry their context (the value of the variables in their local scope) with them on the call stack.

3. Goals for this exercice

We will implement the traditional freshman computer science exercise : the recursive factorial function, in a Rockwell PLC.

4. The crafting

Let us first write the algorithm. This should be pretty familiar :

factorial(n: LINT) returns LINT

if n equals 0 or 1 then return 1

else return n * factorial(n - 1)

You may recognize the same base pattern as the sum() thing we've looked at.

By mathematical definition (and in the case of 0, convention), 0! and 1! are both 1. Therefore, that's my base case, the point at which I can most easily compute a result. The recursive case is any other value or n.

Because we have syntactic limitations, we can already see this will not really be a simple two liner :

- Our subroutine doesn't return anything.

- We can't call our subroutine with an expression input.

That's kind of annoying, but it's just boilerplate code. The hardest limitation is this one :

- A recursive subroutine call has no way to remember its context.

Remember that to use recursion, we have to know what n is in each call. However, because subroutine calls share memory, each call will overwrite the value of n. When we hit the base case and unwind my call stack, n will be 1 and all we will achieve is computing 1 * 1 n times, which will obviously be 1.

Therefore, to use this recursive algorithm, we need a way to remember what the value of n was for each call. This would mean that the call stack should also include the context (that is, the value of the variables in the scope of the function class), which in a traditional PC is what happens. However, we already know that the call stack on a Rockwell PLC does not include the context.

We could create a new stack data structure storing the local context for each call, but because this algorithm is so simple, we can actually manually restore the context, saving us the trouble of handling a stack.

Our solution :

SBR(n);

IF n = 0 OR n = 1 THEN // base case

RET(1);

ELSE

n := n - 1; // preparing for next call

JSR(Factorial, 1, n, r); // recursive call

n := n + 1; // context restoration

r := n * r; // using returned r to compute current r

RET(r); // return current r

END_IF;

If we try it with n = 5, we get 120. Great! If we try it with n = 26...

MAJOR FAULT

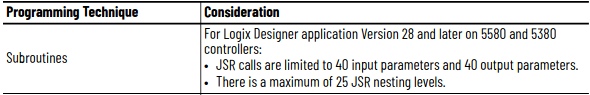

As it turns out, Rockwell's stack depth (the nesting limit) is 25, as seen in the documentation.

We should note as well that even with a LINT type, the factorial of 26 (or 25, or 24) cannot be held into memory. The maximum that could be held is 20!. Because this is a signed type, we overflow in the negative.

5. Fine-tuning

With our current solution, we could have an index counting the stack depth and forcing a return with some error code if we go past that 25 nested calls limit. Let's do some modifications. We will need to introduce a global "call index" i.

SBR(n);

i := i + 1; // coming into the call, increment stack index

IF n = 0 OR n = 1 THEN

i := i - 1; // leaving the call, decrement stack index

RET(1, 0);

ELSIF i >= MAX_STACK_DEPTH - 1 THEN // MAX_STACK_DEPTH = 25

i := i - 1; // and again

RET(1, -1);

ELSE

n := n - 1;

JSR(Factorial, 1, n, r, err);

n := n + 1;

r := n * r;

i := i - 1; // and again...

RET(r, err);

END_IF;

However, the call stack limit is fixed at 25 of any subroutine call. The above works when i is initialized at 0 at the first scan and when the Factorial subroutine is called from the main routine of a program, as at this point the stack is only the main routine.

In a traditional environment where we are mostly using subroutines to organize code, this would be called from at least one subroutine, and the call of these subroutines would already occupy at least one spot on the call stack. Therefore, each time any subroutine is called, recursive or not, we need to increment i at the start and decrement i at the end.

We can quickly see how this is untenable in the long run and why this is a hack. We rely on our inner discipline to make sure we increment and decrement i when needed. Miss one spot, and the PLC blows up.

6. The end

This little exercise may have seemed pointless because recursion in a PLC is both a bad idea and (with our chosen platform) janky at best. However, we've actually managed a pretty deep dive in how subroutine calls and parameter passing in the Rockwell ecosystem actually works, which is knowledge that we can use for more useful purposes.